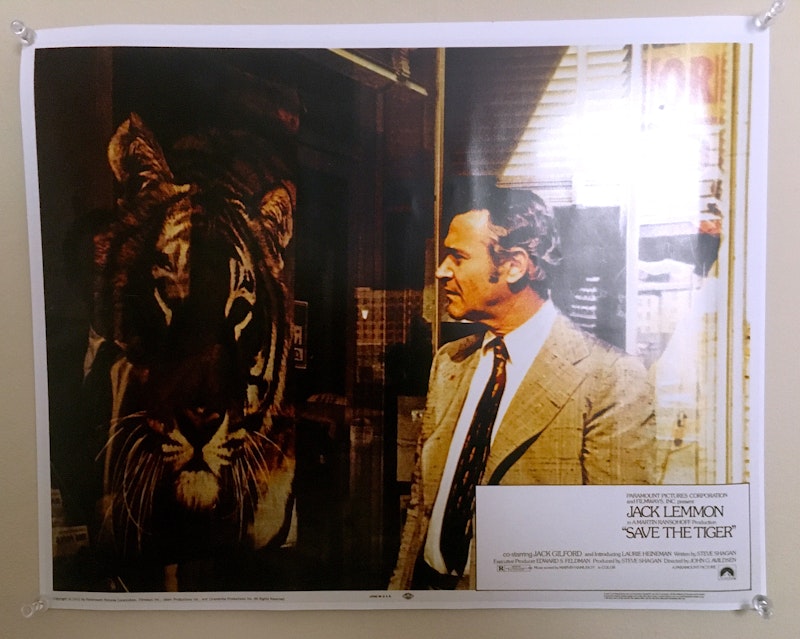

Usually when I'm getting dressed or waking up or reading in bed I get distracted and look at this picture of Jack Lemmon in Save the Tiger. This print is pinned to the wall opposite my bed, a promo still of a brilliant moment where Lemmon's character, a scummy garment factory owner, stares at this painting of a tiger on a Los Angeles sidewalk. The movie begins with Lemmon waking up screaming in bed—by this point, he's already drained. He's just agreed to torch his own facilities for the insurance. Save the Tiger is one of the bleakest American bummer movies, released in early 1973 when disillusionment, disenchantment, and destruction were firmly entrenched across the country. So many years into the Vietnam War and still two years away from its official end, the weariness of this period—and the lack of guidance, much less answers, from authority figures recalls the present.

This image is from the last third of the movie, after Lemmon has agreed to pay a professional arsonist to do the job. Clean, but expensive—and discreet (Thayer David nails the part, all pervert Laughton and stone menace). Lemmon walks the streets of Los Angeles in a daze, so confused and full of shame, unsure who he is anymore. A hippie calls out: “Hey man! Save the tiger.”

His lull is broken for a bit, he picks up a pamphlet, and then he stares at this image of a tiger. The tiger—and it’s up to him to save it. In fact, if we all do our part, we can all save the tiger, and it’ll all be because of us! But hey, even if we don’t save the tiger, I sat out here all day asking—no, begging people to save the tiger. You should’ve heard the things people said to me. But those people that listened, that looked, that took and read the pamphlet, they helped, too. They helped make sure the world knew we wanted to save the tiger.

Save the Tiger was my late uncle Jeff’s favorite movie, a case of kismet when he saw it on original release. He never torched anything, but as an affluent businessman approximately Lemmon’s age, this was essentially a catalogue of quotidian problems and annoyances. Only 100 minutes, with no resolution and an end point that reframes the entire film. Save the Tiger’s sudden conclusion, after the payoff but before the arson—the credits roll over Lemmon watching a Little League game—makes a bleak movie even bleaker: cutting off this event makes it just as insignificant as picking up dry-cleaning or figuring out next quarter’s budget. Insurance fraud is another everyday occurrence, like waking up screaming in your single bed while your wife sleeps soundly somewhere else in the house.

But I look at this image every day and the particulars of Save the Tiger disappear. It’s not important that Lemmon sells shirts, or how much he’s in hock, or how awkward and “uncool” he is. Early on, Lemmon picks up a hippie girl in a scene that Quentin Tarantino probably lifted for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: near where Brad Pitt met Margaret Qualley on that glorious February day in 1969, Lemmon picks up a young woman who asks him if he “wants to ball.” Lemmon blanches, embarrassed and confused, and of course he doesn’t take her up on the offer. He’s clearly curious, but this isn’t a movie of new beginnings or star perversions. It’s not a movie of movement, really. Save the Tiger is 100 minutes of painful stasis stranded in the desert of middle age, a drawn-out world of suspended possibility that feels more like a dream than most things you'd call "surreal."

And I’ve been thinking about this image lately because it’s the point where Lemmon’s personal demons give way to the miseries of the world. The environmentalist trying to save the tiger doesn’t give him a hard time; he’s just as checked out and clueless as Lemmon. He stares at that painting in the window forever, and then we’re onto the next scene. Saving tigers doesn’t come up before or after this brief scene, and yet the movie takes its title from this mostly wordless exchange. It’s a metaphor for meaningless displays of charity and kindness in a world that doesn’t allow for moral justice. Lemmon’s so far removed from a position where he could actually save “the” tiger, that all he can do is stare helplessly at this platonic representation.

Lemmon’s not an arsonist; it’s simply “what has to be done.” Ending before the event underlines what this movie is about: to succeed in America, one must sell one’s soul. One may lay all moral turpitude and beliefs at the feet of capital, so that the massive machine can continue producing and exporting waste. Lemmon’s disenchantment, his unhappiness, is less severe and acute than that of his underpaid immigrant workers, but it’s a psychic wound from the same vampiric society we’re all born into. No wonder Lemmon won an Oscar for his performance, it’s a great heel turn (though we were still cheated out of an even greater about face, Jack Lemmon as Paul Kersey in Death Wish only a year later).

What can one do without a paddle? Lemmon’s character is on a one-way track to Hell, or at least oblivion, and that state of mind is unavoidable now in America: a desire to help, to do something, whether it’s for yourself, your friends, your family, or your neighbors. But where to begin? Anyone?

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith