Former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley (D) is more accustomed to winning than losing. His long and successful career in elective politics has been a series of victories and a single near-miss that began in the frozen cornfields of Iowa in 1984 and may signal a major setback now in the snow-packed state where he once before engaged in a losing campaign. The decision O’Malley must make is whether to soldier on or to call it quits.

It was more than three decades ago that O’Malley, as a 20-year-old college student, earned his organizational chops in Iowa as a door-to-door leg-man promoting the long-shot presidential campaign of Gary Hart. For almost a year he’s retraced those campaign trails and isolated towns to advance his own candidacy for president, only recently to a single soul who showed up on a frigid night to listen and then decline to commit. Such is life on the road in the nation’s first primary (caucus) state where the sorting-out begins and candidacies end.

Many candidates stay in the race one primary longer than they should. O’Malley, despite his low standing in Iowa, has cause to push on to New Hampshire. There he has friends and support and has spent a good deal of time, the same check-list he thought would boost his candidacy in Iowa. But in all the planning, war-gaming, calculations and organizing that go into the commotion that eventually coalesces into a campaign, there was one unforeseen obstacle that O’Malley and his whisperers could not possibly factor into his formula for winning the Democratic nomination: Bernie Sanders.

With his thunderclap populism and anti-establishment persona, Sanders was able to elbow O’Malley aside and occupy the party’s ideological left, the cohort that O’Malley had hoped to claim as his passport to, if not the nomination, then a respectable performance. Sanders even forced Hillary Clinton to recalibrate her campaign to adjust to the new unanticipated threat from the left and what is usually characterized as the Obama coalition. O’Malley was never able to catch on or catch up.

And now, once again, Sanders will upstage his youthful rival on the party’s left flank, in, of all places, friendly New Hampshire, the Vermont senator’s next door neighbor, where Sanders eclipses even the party’s front-runner, Clinton, in every poll. From there, the primaries head to Nevada, South Carolina, and, along with that election, to the Southern regional primary where O’Malley would seem to have little or no chance of sustaining his candidacy where huge black populations favor Clinton.

So what happened? O’Malley, at 52, was supposed to be the wunderkind of this election cycle, the youthful candidate representing a new, upstart generation and a fresh cyber approach to governing. O’Malley was a largely successful governor with an impressive record of progressive achievement. He was recognized nationally for his work on homeland security and his high-tech system of government accountability, State Stat, and before that, City Stat, as mayor of Baltimore. And he was recognized for his leadership by the toughest critics possible, the nation’s Democratic governors, who chose him twice as their national chairman. He demonstrated superb organizational skills in his four local campaigns—two for governor of Maryland and two for mayor of Baltimore. (O’Malley lost his first campaign for the state senate by 86 votes.) He ran a squeaky-clean administration without even a smidge of a smudge. And he was somewhat of a local celebrity as front man of an eponymous Celtic rock band, O’Malley’s March, in a black muscle shirt that elicited androgynous oooohhhs and aaaaahhhhs over his pecs.

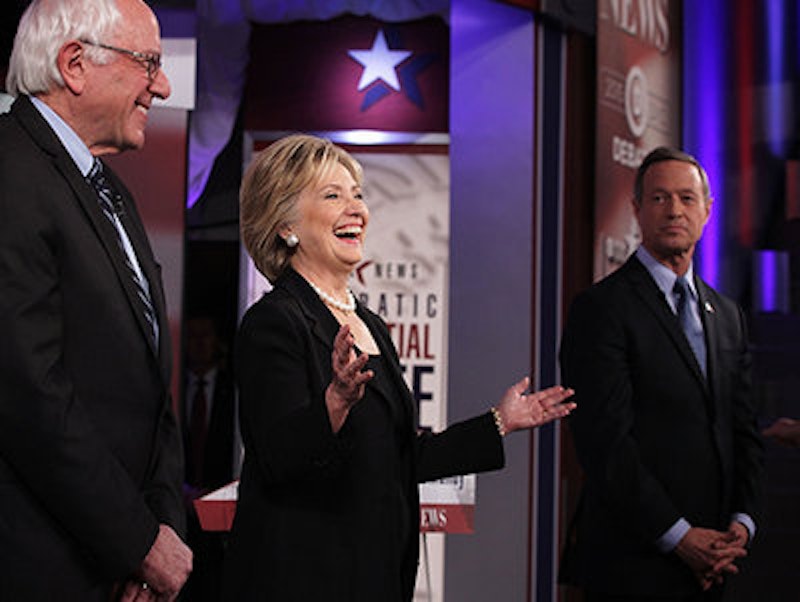

Yet the telegenic rock star was upstaged by a 68-year-old grandmother and a 74-year-old rumpled hippie socialist/Democrat with fly-away corn silk hair.

The overly as simple answer is that 2016 just wasn’t O’Malley’s year. He’d planned his campaign as a youthful alternative to Clinton even though he’d supported her in 2008. But the public was in an unforgiving mood. This was the year of the message more than the messenger. And Sanders had caught the same wave of anti-establishment fervor as had Donald Trump on the Republican side of the discontent. O’Malley, at his peak, never punched higher than five percent in the polls.

O’Malley didn’t benefit significantly from the debates. His content was always solid but his presentation was often unsteady. That said, more often than not the debate moderators were driven to create flashpoints between Clinton and Sanders, the two frontrunners, denying O’Malley equal participation and camera time. O’Malley has clamored for more debates, implying, if not suggesting outright, that the debate schedule had been rigged in favor of Clinton. He wasn’t alone in that observation, including the Sanders campaign. The debates were mostly scheduled off prime time and on weekends when audience numbers are reduced.

And now it’s Clinton, in kind of a role reversal, scared in Iowa and behind in New Hampshire, who’s agitating for more debates, preferably as early as this week and primarily against Sanders. And in another dipsy-doodle, Sanders, who originally joined O’Malley in the call for more debates, is holding out against Clinton, who had objected to O’Malley’s proposal. Frontrunners rarely want to debate because they have the most to lose. That says a lot about the onset of panic in Clinton’s campaign.

More to the organizational point, Iowa is a caucus state, as every political hobbyist knows, where the rules of engagement are complex and the turnout uncertain. The caucuses, truth be told, are more of an economic development program than an electoral system. They require months of legwork and an army of ground workers to ferret out and identify participants who are willing to turnout at seven p.m. on caucus night at school gyms, church basements and fire halls.

In campaigns, money is staying power. It takes a ton of money to finance such an organizational effort and this is where O’Malley fell woefully short. He could not compete with the millions Clinton had raised and the thousands of small donations that poured into Sanders’ coffers daily. Nor did his consistently low standing in the polls provide the motivation needed to encourage campaign contributions. So a few months ago, O’Malley had to do the painful but inevitable. He was forced to cut salaries, reduce staff and pare back his ground operation in Iowa where what counts more than anything else is the headline following the caucuses and the momentum it generates, i.e., a strong second-place showing is often more favorable than a narrow winning performance. Here O’Malley’s fade-out begins.

There are those who believe O’Malley was in the presidential race as an ego trip. But take it from those who’ve done it, nobody considers it fun. And there are those who believe O’Malley was playing the long game, wherein at 52 he’ll be first in line four or eight years from now. Or vice president. Or a cabinet slot. Or a few delegates he could broker at the convention. Or he was auditioning for a talking head slot on TV. Or—and hold your breath on this one—he can run for governor again now that his two consecutive terms are over and there’s a gap between service. Probably any or all of the above is the answer.