Foreign policy questions are often presented in terms of U.S. national interest vs. U.S. moral obligations. Zack Beauchamp makes the case for framing them that way in a recent piece indicting Kissinger's realpolitik of cynicism and genocide. For Beauchamp, Kissinger's primary sin was the idea that "the United States is justified in doing anything… if it furthers America's 'interests' in some vague fashion."

I'm all for kicking Kissinger in just about any context. Still, I don't think it follows that because Kissinger was a bastard, considerations of national interest will always lead to worst outcomes and/or lakes of blood. On the contrary, the moral stance in foreign policy that Beauchamp advocates leads to crappy outcomes just as often. As Damon Linker perceptively argues, in the U.S., our "nation's founding documents and civil religion conceive of democracy in emphatically moral and universalistic terms." Pacifist theologian Stanley Hauerwas makes a similar point when he points out that:

American wars are justified as a ‘war to end all wars,’ or ‘to make the world safe for democracy’ or for ‘unconditional surrender’ or ‘freedom.’ Whatever may be the realist presuppositions of those who lead America to war, those presuppositions cannot be used as the reasons given to justify the war. To do so would betray the tradition of war established in the Civil War. Wars, American wars, must be wars in which the sacrifices of those doing the dying and the killing have redemptive purpose and justification.

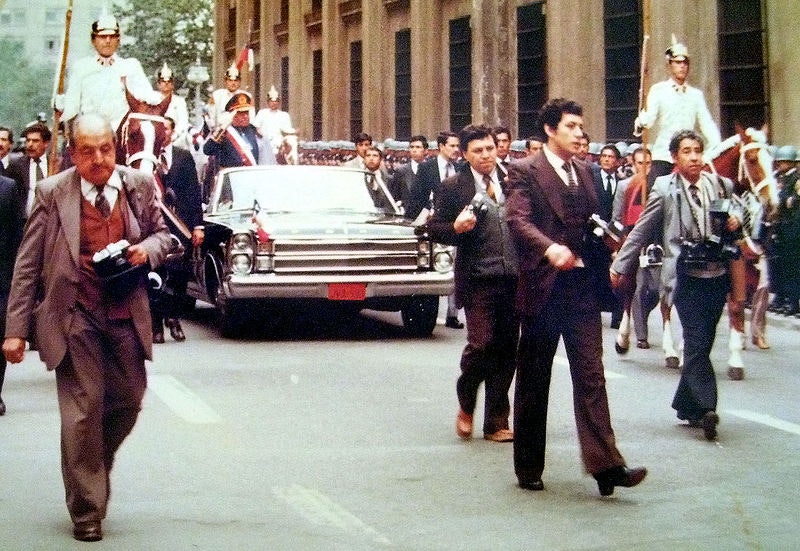

This is true even for Kissinger. Anti-communism was not justified on realpolitik grounds, but rather on the grounds that Communism was evil, and that it was up to the U.S. to save the world from this totalitarian threat. Kissinger's most famous quote about Communism—"I don't see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people"—frames support for Pinochet's Chilean thugocracy not in terms of realpolitik, but in moral responsibility. The U.S. supports Pinochet not (or not just) because it's good for us, but because it's the responsible right thing to do, whatever the Chileans may think.

You could see Kissinger's appeal to some sort of universal responsibility here as simple cynicism. All he really cares about is U.S. interests; the moral talk is a scam. No doubt there's something to that. But moral language in the name of someone else's interests very often has a ring of hypocrisy—especially from the mouth of state representatives. As Linker says, there is "a fundamental distinction between morality and politics." Morality deals with universals. Politics deals with constituents; it's about interest groups, voters, and stake-holders.

Politicians are meant to be accountable to the polity. They're good at being accountable to the polity. They're not so good, however, at being accountable to people on the other side of the planet. There are no mechanisms whereby different interest groups in Iraq, for example, can reliably signal the U.S. President as to whether an invasion is likely to improve their lives or the reverse, just as Chileans didn't have very many levers by which to hold Kissinger to account for his decisions. In foreign affairs, U.S. politics may reflect the moral choices or the national interests of U.S. citizens. But either way, it's not going to reflect the national interests of anyone outside the U.S., because those people don't get a vote.

This is the great moral principal on which the U.S. was founded—no taxation without representation, which is to say, people thousands of miles away don't get to make decisions about your life. The U.S. has spent over 50 years violating this principal, dumping more and more money into the military until America just about can't help itself from putting its nose, and its bombs, into every conflict on earth. There's no easy solution to that. But rather than arguing over whether we should bring out the guns in the name of morality or national interest, maybe we could acknowledge that, as a nation, if not as individuals, our politics are ill-suited to address the concerns of people who do not vote in our elections. And as a result, we should think twice before we start shooting anyone for their own good.