“Hypocrisy,” La Rouchefoucauld tells us, “is the tribute vice pays to virtue.” But it’s often difficult to distinguish between hypocrisy and self-delusion—between someone trying to pass as virtuous, and someone who earnestly believes they’re virtuous even at their most vicious. That’s perhaps especially true in a head of state. Bearing that in mind, consider the phenomenon of dictator literature: the tribute power pays to philosophy.

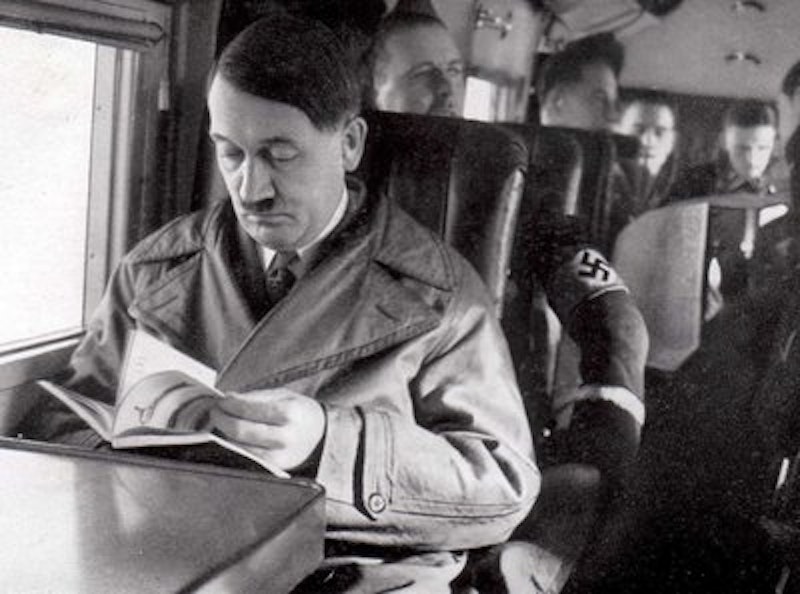

Daniel Kalder’s recent book The Infernal Library is a critical reading of the writings of tyrants from the past hundred years or so, in all their varied forms: theoretical works of political science, poetry, fiction, autobiography, and more. All of it, in his assessment, dreadful. Men in absolute control of their country, shapers of their own reality, extended their belief in their own infallibility to the delusion that they knew how to put words together. Then, having written, they commanded that their works be distributed and read by nations they imagined were awaiting enlightenment by their various hands. They controlled the lives and deaths of millions of people; but it was important they be seen as thinkers. Important that they put forward their philosophies of life, the world-transformative missions each imagined themselves possessing.

Dictator by dictator, Kalder analyzes the various texts of this odd corpus. He puts the writings in their historical context, and shows their influence. His first section, “The Dictator’s Canon,” deals with perhaps the five most notorious dictators of the 20th century—Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler, and Mao. Part Two, “Tyranny and Mutation,” presents shorter overviews of a range of dictators, with each chapter considering pairs and clusters of writers: Franco and Salazar, Atatürk (a rare benevolent dictator) and Nasser and Gaddhafi (with the œuvres of Mobutu and Francois Duvalier briefly noted), Kim Il-sung and Enver Hoxha and Leonid Brezhnev. Part Three is about dictators of the post–Cold War world, Kim Jong-il’s cinematic dreams and Saddam Hussein’s historical romances and the historical-philosophical fantasia of Tajikistan’s Emomali Rahmonov.

It’s a brisk book, resolutely non-academic, terse and often bitter. Easy to see why, again and again, Kalder describes an incredible waste of human life, whether through outright genocide or the deprivation of hope and freedom on a national scale. And, an incredible egocentric belief on the part of a dictator in his own greatness. Dictatorial writings, in his reading, always reveal an infantile egomania, a belief in the writer’s rightness, in a universe with the writer at the center. If that sometimes happens in the work of non-dictator writers, there’s much more of a surprising uniformity in the terrible quality of this work. Being a dictator means nobody can give you constructive criticism.

Kalder’s idea of dictator literature as a specific form with its own canon is intriguing. And it’s at least nominally possible to argue that the experience of dictatorship is so specific and transformative that a writer will be shaped by it in particular ways. Kalder doesn’t advance a specific theory or definition of dictator lit. You can see some commonalities: these writers are all men, for example. And military backgrounds are common. But Kalder refrains from developing any kind of theoretical structure for analyzing these works. He’s evaluating them as writing, not examining them for shared characteristics.

As such, his book is entertaining and intelligent. Kalder organizes what seems at first glance a divergent mass of material intelligently and even naturally. His analyses of the texts of the dictators are piercing and convincing. It even leaves a reader curious about some of these books: I’d be interested in reading Hussein’s romances, or at least skimming them, and more so in glancing at Mussolini’s diaries of World War One, one of the few works Kalder judges a partial literary success.

One might quibble with some of Kalder’s choices, notably about what dictators to exclude or to pass over quickly. It’s worth noting that he has an uncharitable reading of Marx, whose political invective at least I find readable—but then, unlike Kalder, I’ve never lived in a country that spent decades under a dictatorship informed by Marx’s ideas. I do wish Kalder had specified what languages he reads; he mentions living in Russia, how and where he read some of the translations he works from, but in some other cases I’m unclear whether he read the dictators in the original or in English.

Either way, his readings do suggest some insights into the psyche of the dictator. As do his lived experiences. In discussing Rahmonov’s encyclopedic Rukhnama, a mix of autobiography, revisionist history, myth, and religion, Kalder describes visiting Turkmenistan and seeing the ubiquity of the book while Rahmonov was alive. Billboards. Stones on a hillside spelling out the book’s title. A giant monument in the shape of the book that was supposed to open every day to a new page (the mechanism broke, and was never repaired). A library with a reading room dedicated to the one book. A televised concert in which the book was read aloud in several languages. Turkmen who told him the book was great, but could not say why. As Kalder says: “[The book] was intensely present: a hallucination I could touch, a lucid dream in pink and green and gold that wouldn’t end.”

A dictator tries to rewrite the world. But their texts are lacking, thin in ideas, deriving power not from the quality of their language but merely from power itself. For Kalder, there’s a contrast worth noting between the word and the flesh: between the purely notional reality of a text and the corporeal reality of the body. He makes the point consistently through the book, and it’s a good one. Dictators’ writing, like their whole career, is a form of escapism. They try to reshape the reality around them into the world they imagine inside their heads. But death is a reality they cannot escape. And their books will not help them.